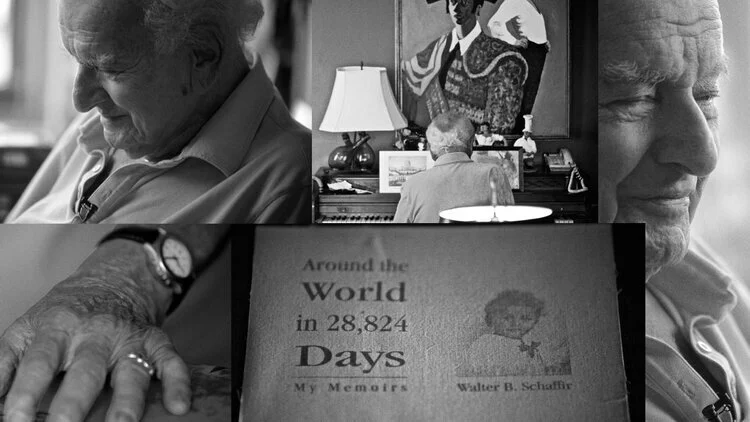

Last week I was fortunate enough to be invited to an art opening of one of the most talented, absurdly under-recognized, smartest and kindest person I know, Fred Terna. (Recent BOMB article on Fred)

On it’s own, this is already an exciting enough event. The fact that Fred’s important, and rarely seen in public, work being exhibited in a formal space is a great gift. Add to that, the chance to see and hear Fred in person and you get a night to remember. Speaking to Fred, one always faces an opportunity to hear words of enlightenment. Which, just like his art, are filled with secret textures, meanings and colors that are not immediately apparent, it’s an effect that is both illuminating and sometimes confusing. This is a feeling I'm very familiar with, one I felt multiple times while working on the film I made about Fred (Shared Memory)

). I started The Ripple Project with a pre-conceived notion of how to portray the social scar caused by trauma, particularly the Holocaust. As the project progressed I realized that in fact, it’s not a scar but rather an open wound.

This idea started to crystallize after spending a few days with Fred. As, so many times with him, you learn that things are not always as they appear. Fred’s words and art gave rise to the idea of fluidity of memory and acceptance of inevitability. He proudly, shows me two, seemingly, completely different paintings. He explained to me that the two are of the same horrifying event he witnessed during the Holocaust. The abstract paintings were painted in different eras, nearly thirty years apart, and their stark difference of color, brush stokes and composition reflects the way the “feeling” towards the memory has changed. The most recent of the two paintings is poignantly labeled: “Shared Memory.”

An idea, that might have been instinctively present in my subconscious has been put on display in front of my eye so clearly. A memory of an event, as horrific now as it was then, but the artist’s attitude towards the memory of the event has drastically changed. Memory is fluid; constantly shifting and moving.The other revelation I had while working with Fred, was an acceptance of the inevitable. On the last day of the shoot, Fred dropped a verbal “bombshell;” He proclaimed, with pride, that had he been given the opportunity, he would not have chosen a more “ordinary” life. According to Fred, had his life been an “ordinary” one, he would have ended up as a: “Crotchety old university professor for historical geography or geographical history.” Fred has no anger, no remorse, no regrets, life has a forward momentum that needs to be lived and experienced with all its twists and turns. My first instinct was one of disbelief, why would someone “choose” to go through the pain, suffering and loss that Fred experienced? My skepticism turned to understanding, when I later heard this idea echo through the words of another grand personality I interviewed (Itzhak Arad)

It’s the journey taken which creates the rich tapestry of life which makes it all worth while. This is a profoundly human and humane idea. It’s these conversations with Fred which helped me see and deal with the trauma of loss from the Holocaust, in a different way, including lessons applicable to my own life.

So when I saw Fred last week, I was hesitant about asking any questions, concerned this is not the time or place to search for “pearls of wisdom” which would again add a whole new dimension to my take on the Holocaust. But, thinking and doing are two different matters and considering these opportunities are far apart the moment just begs for a question to be asked. This was a special evening for Fred. He was outside of his studio, surrounded by his work lovingly hung for people to enjoy (rare) and smartly curated by his son Daniel, who’s an accomplished artist in his own right (http://www.danielterna.com). The place was full of friends, loved ones and admirers, just begging for another chance to see and speak to Fred, who was in top form, but visibly tired. After we embraced and chatted about mutual work, out of the blue, I asked a simple, even banal question: “What do you think about the election...?” I don’t know why I asked him this question or what I was expecting the answer to be. I just really wanted to know what Fred thought. The election left people on both sides of the aisle confused, angry, bitter, frightened and suspicious of each other. It exposed the sharp divide in American society and revealed the thin wires which hold it together. As a person who tells stories of genocide it left me scared that once again, irrational fear and anger can shatter a fragile society. Fred smiled at me, the kind of smile that says “you asked for it kid...”

He closed his eyes for second, as he often does before he begins to speak, as if to enhance the drama. Tilting his head right and with a wry smile said: “I’m disappointed, confused, and surprised but not worried. Dictators don’t last, it’s against human nature. We just need to keep our civility.” I looked at Fred with puzzled eyes, where was the anger? The fire? So I followed up with another question: “Civility? At this time? Who cares about that? People are angry now.”Fred responded in a deeper tone, the smile was gone: “When we were in the camps, facing death, humiliation, starvation, anger, not knowing if we will live another 10 minutes… we still kept our civility. We always knew the Nazis wouldn’t last, it’s against human nature. It doesn’t matter what the Nazis did to us, how much they screamed and yelled at us. When we were alone in the room, at night, we were civilized. We knew that our civility is the key to survival, our humanity and civility will outlast the Nazis. It might take a month, a year or ten, but it will outlast them.”

Fred did it again, in three sentences he was able to refine, and perhaps redefine my perception of civilization and humanity in a time of crisis. It allowed me to put my fear, anger and confusion in check. It’s not just about the survival of the body, but one of soul, this is a lesson that transcends something larger than our imagination, as the Holocaust, but is also valid in our everyday struggles.That night I went home, hugged sarit, the kids and found some serenity.