A life close to a sorrowful end, marches on with laughter.

Late Night

“Why am I here?”

“What is my value?”

These banal questions are just a sample of a daily brain storm during my personal COVID middle-class existential crisis. At this point my family and I are the lucky ones; not hungry, ill, or in dire-straights. Just stuck at home with no routine, less work, less bicycle, air, sun, friends and privacy. I am left, in my basement editing room to look within. This forced-upon-us new reality has given me much early anxiety. I am not a person who likes the unknown, or an un-calculated adventure, and this sure feels like one.

I always lived with the idea that I have some control over my life. “Do some home budget spreadsheets, save for retirement, stay in shape, eat well and try to live a long life.” Seems like a good plan. I’m aware things can happen, but all within calculated risk. This COVID crisis, is a start of a new unknown reality and future. It came as a storm, with not much one can do to prepare. When the world began to shut down slowly, I felt that my breathing got uncomfortably quicker. Are we gonna stay healthy? Will I work? What will be of my kids’ education?

Viewing Itzhak Ginzburg interview (1995) , Brooklyn, NY. 2020

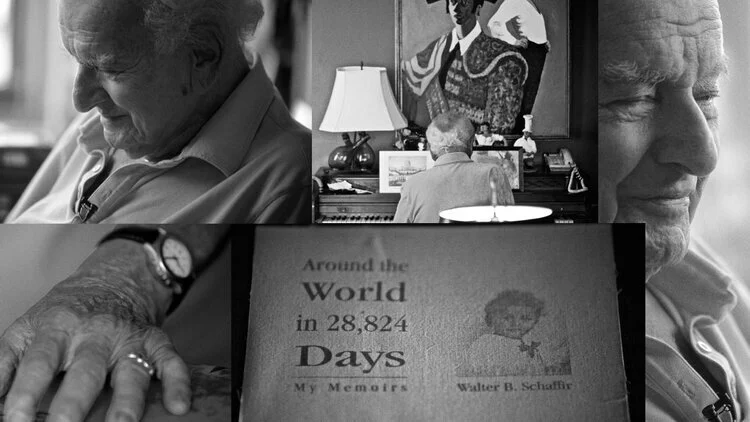

A few nights ago, I had a hard time falling asleep, thoughts of the next morning, week, or month keeping me up. As the night grew longer and darker I found myself drawn to a particular story my grandfather told me. It’s how he survived the coal mine labor camp in Kazakhstan, in 1942. I couldn’t really put my finger on why this memory has reawakened in mind on a sleepless night. I recalled this as a sad story of near death experience and famine. That same night I sat down for a re-listen. Itzhak’s raspy voice was retelling a story I knew, but the impression was different than what I recall from when I first heard it. It’s actually a story of embracing the lack of control over one’s life. Itzhak, who believed his war injury would help him avoid further Russian front line placement and send him some relief has instead been handed a cruel card. He was sent to a notorious labor camp that many don’t survive, yet he did, but not in an obligatory manner of heroism.

Viewing Itzhak Ginzburg interview (1995), Brooklyn, NY. 2020

Where one would expect a grand escape or a moment of breathtaking twist and turn, actually lies a story of surrendering to the elements and relying on ones past, upbringing and instincts. It either took tremendous courage or just a complete surrender for Itzhak to refuse taking that elevator to the belly of the coal mine. I can’t even begin to imagine the stress and pressure of that moment. “What would I do?” “Would I even be able to think? Or just follow?” Life has served Itzhak another drastic T-junction, one he could not have prepared for and he acted instinctively. Itzhak allowed his upbringing and culture memory to take over. He was not a laborer by trade, but a scholar. His instinctual decision to take death over going down the mine, ultimately led to his survival. A memory of an idolized grandfather provided him with last gasp of inhuman energy, reminded him of his true talent in life, and an instinctual gesture of humor did the rest.

Viewing Itzhak Ginzburg interview (1995), Brooklyn, NY. 2020

The reason I love this story is the reminder that sometimes life is not about control, or about calculation. Sometimes its about instinct and some luck. Just like Itzhak staring at a broken mirror in a large room somewhere in a coal mine camp in Kazakhstan, present time of social isolation is our chance to look within. Time to reflect, analyze and find our internal strength, so we can nurture and follow it.

Viewing Itzhak Ginzburg interview (1995), Brooklyn, NY. 2020

This is the magic in this small story, plus the joke at the end is hilarious. Stay healthy. Stay safe.

The following is the segment of the 1995 interview I’m referring to..