A few nights ago, on what seems like another meal, in another day, in a life that loops rather than move in a straight line, I looked at my wife and kids and thought: What would be the memory of these days of forced isolation? What type of memory would I, Sarit and the kids take from this time? After all, we are lucky with food and health, for the time being, and this might seem like a blip or an adventure when this is all over. Would this time be remembered as a happy one? I guess much of it depends how it all ends. Is this the calm before the storm? Are we about to face more adversity?

These ordinary thoughts feel no more than annoying mosquito bites. Besides scratching, not much can be done about them. These meandering thoughts started connecting to another part to Itzhak’s (my grandfather’s) story, the story of Shabbat (Jewish day of rest).

View from a bus – Suburban MD. USA

I always catalogued this particular story under: “sentimental." It's a personal memory of childhood and a long lost family. At the relatively young age I conducted the interview I didn't find it very relatable. But now, even though Sarit and I are secular, non-traditional, relative to my upbringing, this story carries great weight. The significance of the story is magnified by the fact that we are immigrants in the United-States, have a young family, almost no close (by proximity) extended family and no local “history.” Most of what we are doing now, is new to us, with very little past experience to go-by.

There are several elements that feel current and applicable to me. The first one is of historical significance, one before a catastrophic change. Modern society is experiencing a major shift, due to this virus. Our resolve and our ability as a society to keep our way of life is being tested. Humanity has been through changes many times before and it’s usually the a cycle; a sudden pain, resolve, survival and continuity. Itzhak story is pre Wold War II. These were the last few years Jews had any stability or a sense of security before it all fell apart. Even though, he describes a violent incident of anti-semitism with this father, that would have left me quite traumatized, it is a prelude to his seemingly joyful story of Shabbat. I believe his account of, what seems like, trivial violence compared to the latter atrocities they all suffered, is still meaningful as it was a stark reminder to the family that they were not part of the world they lived in. This makes the rest of the story, of tradition and ancestry, more powerful as the listener begins to understand the security powered by unity of a blood-line, heritage and traditional ceremony. My imagination soars as I see my great-great-grandparents, aunts and uncles sitting together, laughing, conversing and dining week after week finding comfort in each other. It fills me with strength and serenity, not loss. It warms my heart to think that my grandfather experienced these moments, a time he remembered as pure joy. Just as I hope we will remember these days.

View from a bus – Suburban MD. USA

Some troubling questions arise when I listen closer. Are his memories of the past so sweet because he has lost so much? Was reminiscing about these days a painful experience rather than a positive one? I’m frustrated that I will never know.

I wonder why he told me this story in the first place? It’s not a Shoah survival story or a heroic war escapade. After all, that is what I was after when I asked him, all those years ago: “Tell me how you survived?” I like to think he told this story for my sake. I was in my teens living away from home, my parents and my siblings. Maybe he hoped that these shared moments of his past happiness would give me solace, a sense of belonging.

View from a bus – Suburban MD. USA

Living away from my family for so many years, I’ve gotten used to seeing my parents very seldom, or accepted the fact that my kids won’t have a relationship with their grandparents or cousins that I enjoyed. As years go by, I sure miss it. I find myself doing the very thing Itzhak did with me, telling them stories of the past. I off course don’t have the dark gap that he had but still, stories of distant relatives, personal tales of grade school humiliations, sleep-over at my cousins house and other experiences from another era. They love to hear about the strength of their grandfather when he was a “famous” butcher, their grandmother driving a young me, my siblings and cousins across Florida to look for Disney World. I think it makes them feel as if they are not isolated, insulated and alone. What is now my longing, for them is a belonging.

A Mall – Suburban MD. USA

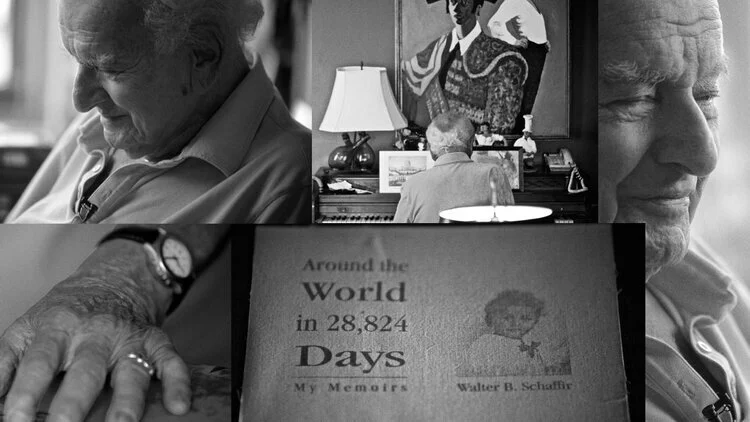

Just a quick note about the song Itzhak is referring to. “Got fun Avraham” (God of Abraham), is an Ashkenazy prayer spoken at the end of Shabbat (day of rest). It symbolizes the start of the week. Shabbat, technically ends when the first three stars appear in the sky. The song describes a child who begs his grandmother not to look for the stars quite yet as he (she) does not want Shabbat to end and the pressure of the new week to begin. As Itzhak reminds us that he was just three or four at the time of the story, I see him as the child looking at his mother. In this case, begging for time to stand still, as if some foresight of awful things to come. It's a complete contrast to the grandfather I saw riding a local bus to a suburban American mall. I imagine him quietly looking out the window, staring at endless strip malls, remembering these moments

The original prayer was written by Rebbe Levi Yitzchak (circa 1800) which shares the same name as my grandfather, which I am sure has added a greater meaning for him.

Itzhak Ginzburg, VHS video. Maryland USA, 1995