I know this post is a few days after Holocaust Remembrance Day (Yom HaShoah), but it's not too late.

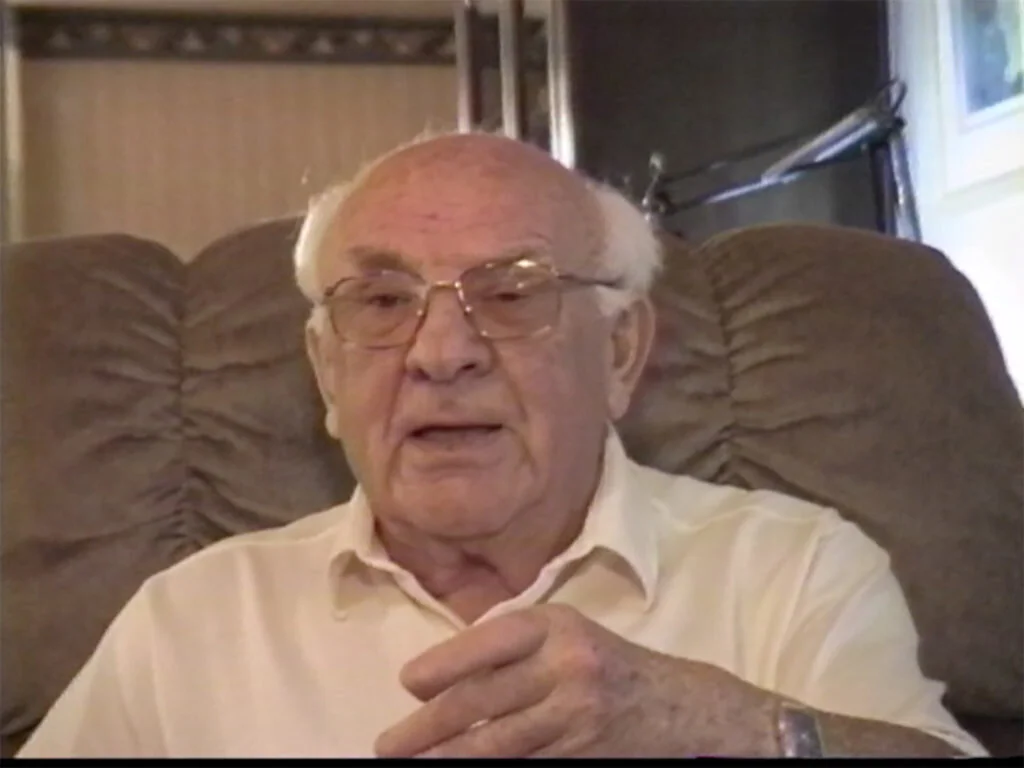

Itzhak Ginzburg, VHS video. Maryland USA, 1995

Through my filmic journey with The Ripple Project, I've met extraordinary people with ever more remarkable stories. Many sad, heartbreaking, but always strangely uplifting and motivating: "if they can survive the holocaust, I can survive anything.” I selfishly think to myself, after most interviews I conduct. I don’t really know if this a defense mechanism to justify my need/want/effort to chase these stories or that true-to-life survival tales are therapeutic. Just as a surgeon has a clinical appreciation and respect for the functionality of the human body, without getting distracted by sight of blood or organs. A therapist can listen to hours of traumatic stories of patients all the while staying calm and helpful.

25 years ago, I don’t particularly recall the reason, I decided to interview my grandfather, Itzhak. I was very close to him, in fact, I would say that my emotional proximity to my grandparents has influenced most of my life altering decisions. I moved to the United States, left a warm home in Israel as a teen, to be close to them. I found my grandfather’s infinitely wise words and my grandmothers warmth to be the most comfortable bed in the universe.

Itzhak Ginzburg, VHS video. Maryland USA, 1995

I remember setting up for this interview as if it was yesterday. I can’t tell if I was more excited with the notion of hearing stories of the past or just the opportunity to mess around with a video camera and a “clip-on” mic. After the initial excitement wore-off, this multi day interview wore me down. I felt guilty as I sometimes began to doze off as my grandfather was talking about labor camps and lost relatives. At the time, the stories were sad to hear, but not sad enough to “feel”. I kept judging my grandfather’s life through the lens of our mutual present. At that point in his (our) lives we lived with my well-to-do uncle (Itzhak’s son), an accomplished artist, who’s rewarded us with a life greater and more generous than either us ever imagined. Living together in an affluent suburb of DC, surrounded by all that makes America alluring to a young Israeli and holocaust survivor immigrant, or so I thought…

Telling a funny story – Itzhak Ginzburg, VHS video. Maryland USA, 1995

Years have passed since that interview, Itzhak passed and I moved away to build my “adult” life in New York. After the birth of my daughter, I became haunted by familiar dreams and memories, but not my own. I initially attributed them to stress or lack of sleep, attributed to “new-baby-zombie” mode.I soon began to realize that they were fragments of stories, scratchy soundbites from that long buried, long forgotten interview. Itzhak’s poetic personal idioms of a horrid past, are now my present.

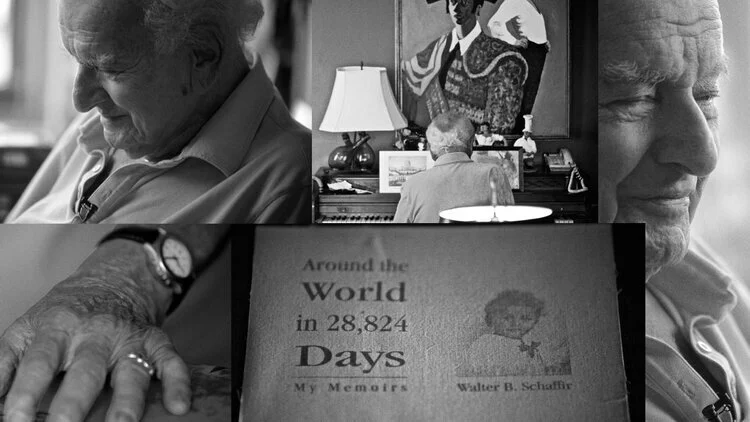

I’ve decided to dig up the tapes and view them, they felt different than my memory of them. I felt what I could not feel before, I saw in him a sadness of the present as much as a sadness of the past, it frightened me. My grandfather’s trauma and loss did not lessen with time, quite the contrary, they seemed amplified. I decided to share them with my grandfather’s dearest friend, writer Herman Taube. For years, I would sit and listen to the two converse, using their oral and written words to keep memories alive. Always amazed at their ability to communicate a deep traumatic experience to someone who’s never been there, stories that felt more fantasy than reality. Herman reminded me that the twilight years were not kind to Itzhak, as depression took over, and night-terrors and tears for loved one lost became a regular occurrence. Seeing the tapes, experiencing his sadness for the first time, I wanted to decipher the chasm between his deep hidden memory vs. his common visible memory, the one we thought we remembered. What lied between a shrouded terrible past and apparent docile years in a quiet picturesque suburb? Itzhak’s past horrors, fears, and sadness were now in me.

Reading poetry – Itzhak Ginzburg, VHS video. Maryland USA, 1995

I was mostly frustrated when I would sit and listen to Herman speak of my grandfather’s past and last days. Herman had an optimistic and happy demeanor, one that felt very contrary to Itzhak, who’s wise jokes and side splitting funny stories in public were always under the shadow of grief, when he was alone. There was always a duality there. A pain reflected in his writing. “Why can’t he be as happy as Herman?” I remember asking my grandmother. After all they both lost so much during the Holocaust and both ended up in very similar geographical and socio-economic places in their latter years. I did hypothesize on this issue many times, and besides a generic “different personalities” answer, I think it also had to do with how they dealt with the trauma. As was my grandfather, Herman was a writer and poet as well, but he was one of documentation. He interviewed, translated, edited hundreds if not thousands of hours of other survivors stories. Just like that surgeon I discussed earlier, Herman allowed himself to see the organs of humanity, he looked inside and saw how its function, maybe that was the tool that gave him the strength to look outside of his own loss and traumatic past.

Itzhak Ginzburg and Liron (reflection), VHS video. Maryland USA, 1995

This revelation began a decade-long physical, emotional and creative journey for me. One, which innocently began with grainy video, family-stories and poorly recorded sound bites. Leading me to reflect upon my own trauma and place in the world. I found myself drawn to storytellers who communicate and deal with their own personal pain via creativity. This is still a journey I am partaking in and I still learn something new everyday about trauma and its elusive post effect.

Itzhak’s haunting words still echo through my life. They keep resurfacing every few years or so in the editing room and in my mind, but they mean something else everytime. Especially, these days of COVID isolation, unknown future and consuming present, they lift me when I’m down, they strengthen me when I feel powerless. His story, his adventure his survival is now ours as well.

Like a stone thrown in a pond, trauma, violently shattering the surface of a calm life. What emanates from one spot, infinitely ripples, to end in the most unexpected of places..

The following is a short segment of the 1995 interview conducted by Liron with his grandfather, Itzhak.