It's hard to describe what it felt like walking into Ela’s house that sweltering summer of 2010. Accompanied by a motley documentary film crew, we were still in the early stages of researching the Terezín concentration camp and had little knowledge of the children's opera Brundibar. My intern found Ela on a google search and was ecstatic when he realized she was in the tri-state area. I made a couple of phone calls, and that same day(!) we packed the car with equipment and crew we were on our way to interview Ela in Tapan, New York. The length of the drive from Brooklyn was basically our research and prep time. The team was comprised of my close friend and partner on the project, my brother who was shooting this interview as a last minute favor, and an assistant, who was only there as a favor for my partner. Ela was the second “official” interview we did for The Ripple Project, and at this point, I wasn’t sure what we wanted to accomplish, we just knew that it was going to be “sad.” I could not have anticipated what was waiting for me when we arrived at a picturesque, modest suburban house.I knocked, the door opened, and a hesitant, slightly suspicions smile greeted us. Ela was a known personality and considered by some to be a “celebrity” within a dwindling community of Holocaust survivors. She had been interviewed, filmed, recorded, talked about, written about, and flown around the globe to share her tale of survival and lessons on life. We were newcomers to the Shoah commemoration world, but Ela agreed to meet us nonetheless. I kinda schmoozed my way to get this interview with her based on promises of things to come. Her disappointment was to be expected.

I jotted down a few fundamental questions while in the car, I was woefully underprepared. Ela was as charming as could be, offered us water and cookies while we set up the room for the interview. Since I didn't know Ela yet and was still unclear about my vision, I figured we would do this one “research” sit-down interview, not my film style of choice, but at least we get to know each other. After a few awkward moments of clumsy back and forth I had a sinking feeling that Ela might be on to us, she would know that we are just a few Shoah "rookies" trying to get our feet wet. I was worried that the interview was going nowhere. I felt a bit discouraged as I sat back and apologetically raising my eyes to look at her, but Ela's demeanor was not what I anticipated.Her voice, tone, and pitch were unphased, as she revealed stories of her travels, adventures, and survival. Ela’s personal story is mostly based in Terezín (Theresienstadt) concentration camp, which is in today’s Czech Republic. She is known as the child who played the cat in all 55 performances of the children's opera Brundibár by Jewish Czech composer Hans Krása. An opera the Nazis allowed to be performed, as the Red Cross visited Terezín which the Nazis set up as a model camp. It’s a complicated story filled with contradictions, a place where children attended art classes while the elders starved to death. It was a camp where music was allowed while the Nazis prepared transits to death camps. These are facts, and the stories surrounding them bring on feelings of sadness, anger, and loss when I think of them. But during my interview with Ela, I felt as if I was not able to access any of these predetermined emotions. I was about to conclude this very brief encounter, but Ela did not react as I expected, knowing her past and having grown up in a family of Holocaust survivors.Ela was happy, Ela was joyous, Ela was filled with life, Ela was proud to tell her story, Ela was performing and we were the audience. This was not what I was programmed to capture; I grew up on Lanzmann’s Shoah, on my grandfather’s guilt-ridden heartbreaking poetry of family lost, on Maus… this was not supposed to be like this. I thought to myself, “she’s a survivor, stories of her past must flood her with sad emotions and sink her into despair.” But this was not to be. Ela was something different, and when I realized that, a calmness settled in. From this point on the interview changed, the room changed, the team around me changed, we were no longer a last-minute put together crew confused about what we are doing but rather a captivated audience listening to a live-play dramatic story.

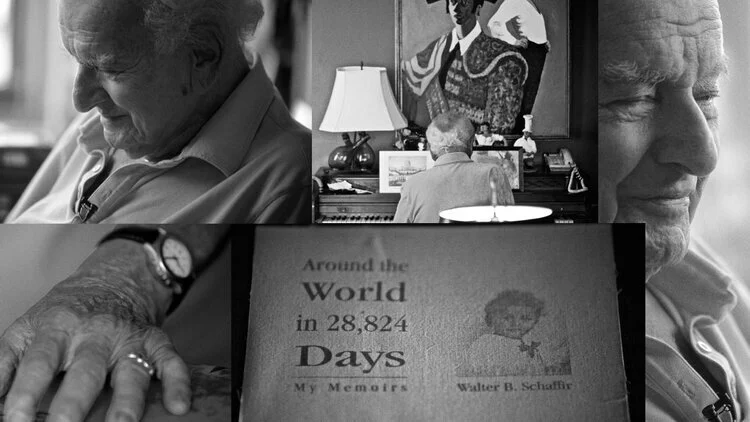

Ela had a gift. Ela's light shone bright, she energized the room and told stories of art, love, teenage confusion and friendship under the worst of circumstances. Ela humanized a time that was, and an experience that she made clear "beyond imagination". She told us little tales of holding hands with a boy, she told us about a how a gesture of make-up, to draw cat whiskers, before the play allowed the imagination of a child to run free, she told us of the connection and bond the kids formed, which made the death of her childhood friends even more devastating, she told us about the ultimate sacrifices of her teachers. Even though Ela’s story of survival might seem by some as less “horrific” than others due to her staying in Terezín, her loss of friends, relatives, and childhood are real.For Ela the show never ended, the stage was endless, and the lights were always on, only the audience changed. After the interview concluded we stayed at Ela’s for a few more hours, we got a tour of family photos, memorabilia, saw and held her Jewish yellow star and more and more stories. A friendship was formed between us, one of the gossipy calls, to receiving a hand-knit sweater as my second child was born. As I struggled to come to terms with the vision telling Shoah stories and the harsh reality of documentary financing, I could always rely on Ela telling me about her recent travels, the interest of certain book writers, movie directors, and TV producers. In Ela’s world, we were all a captivated audience, listening and watching the retelling of the story of this little show called Brundibár and its doomed child stars. It makes me happy to know she dedicated her life to giving voice to those young voices who could no longer speak.And I find peace in knowing there were so many audiences that handed Ela the microphone so a few more lucky people could hear and feel a story of the human spirit’s triumph over unimaginable evil.

I never ended up working with Ela on the film we wanted to complete, we never shot another frame, but that is OK. As for me and my journey, Ela has given more than I could have imagined. Her memory and words have given me enough strength to tell the story of many others. Ela would be happy to know that the show will go on.

Ela Weissberger June 30, 1930 – March 30, 2018 Here is are parts of that interview we conducted with Ela in her house

Ela Stein Weisberger was 11-years-old when she landed the key role as “the cat” in the children’s opera, Brundibár, performed by and for Jewish prisoners in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Ela is the only performer alive today who acted in all 55 performances, and she continues to devote her life to telling the story of Theresienstadt throughout the United States and Europe. Ela shares the tales of her survival, her role in the opera and the lengths to which she has gone to preserve the stories of those who did not survive. Filmed in Tappan, New York, USA, 2010.