There is a magical scene from a kids beloved film My Neighbor Totoro, by Hayao Miyazaki. Two young heroines, Satsuki and baby sister Mei, are standing in the pouring rain, much too late at night, at a bus stop in the middle of the forest. They are waiting for their father to arrive home from visiting their sick mother in the hospital. A sad moment. Next to them stands a larger than life gray, furry and cuddly creature, called Totoro; the guardian of the forest. The pouring rain soaks the helpless Totoro, yet it remains to protect the girls. In a wondrous exchange, Satsuki, gives it her dad's umbrella, which the Totoro uses to its amazement and delight stay dry. Watching this sweet scene with my kids fills me with pleasant sadness. Of all modern life riches available to them, they mostly rely on their parents for help and assurance. They will probably never know the unconditional comfort and confidence given by an angelic presence outside of Sarit and I; this is the curse of being kids of immigrants. I, on the other hand, was privileged to be enveloped in this magic, time and time again, my Totoro was my grandmother, Lida Ginzburg.

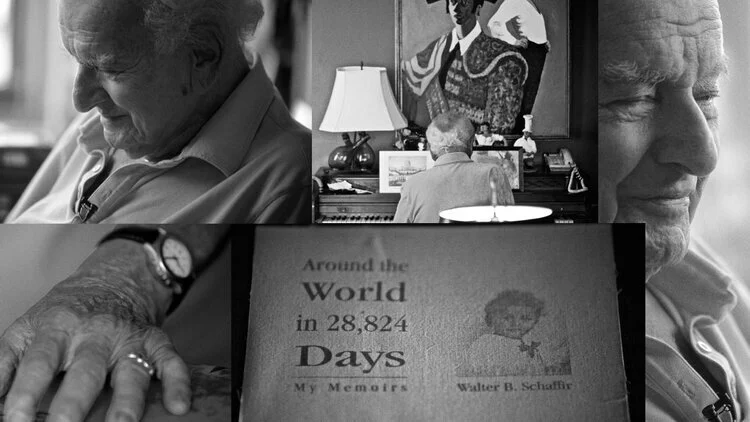

- Lida has passed today. -

Lida - Jerusalem, Israel

At the age of 15 I followed my maternal grandparents from Israel to the United States to live with their son (my uncle) and his family. I was so close to my grandparents that ripping away from my immediate and loving family felt like a predestinated decision following my their departure. I recall the first day of American high-school, armed with remedial English, I was set to face the consequences of leaving the familiarity of home. I woke up extra early in an un-Israeli rainy, cold and dark morning. I headed towards the intersection without a hint of what to expect of my first day. The streets were empty and foreign, the smells nascent, the houses large and strange, the color of the early morning unfamiliar as I marched towards that bus stop. I stood there, alone, awaiting for that mythical yellow bus, which I've only seen before in movies and TV. It began to rain. As an Israeli teen, I was, naturally, ill prepared for any weather but “nice.” I was about to get soaked on my first day of school. A few seconds later a murky figure appeared out of the dark fog, it was Lida. She, very quietly, followed me to the bus stop to make sure I arrived, and by chance she had an umbrella with her.

Lida and Liron - Maryland, USA

That first American winter brought on many lonely and friendless nights, that would end with a late hour knock my door asking if I want to go the local diner for a milkshake. Marching through the snow with Lida felt like a warm walk on the sand. Stories of life pre, during and post-war made me feel unique, brave, special and not alone. Her presence has been there throughout my whole time there, and rewarded me with strength and daily courage.

Some of you know about my grandfather, Itzhak, and my personal and professional admiration for him. Yet for some reason, it’s the memories I shared with my grandmother which are most personal and cherished.

Lida and Bella - Bat-Yam, Israel

As a young child, I would profess to having enjoyed staying at my grandparents' more than at my own home. It was a place to escape, a place of quiet, wisdom and pecan ice-cream. I remember long nights of laying in bed by Lida as I try not to sleep, counting moving cars headlights filtering through window shades while listening to Polish and Russian folklore tales, again and again. I still, today, stubbornly practice this routine of caressing and story-telling to my tween daughter. Trying to pass on some of the what I felt laying on that bed.

Lida - New York, USA

Besides the fables, Lida was truly a heroic, infinitely energetic and powerful matriarch; when her son, eight years old, fell to a rushing, freezing river only to be saved by a mother's super strength, as she dove in to pull him to safety. In another time, Lida, rushing through a kids' summer camp in Poland, looking for her twin daughters after being notified that a typhoid outbreak has broken out. Not giving up until she broke through and saw them safe, with her own eyes. Years before that, Lida was told she is having twins, at a time where her and my grandfather could barely afford to feed their one growing boy. She fought and resisted calls to abort the pregnancy by her own husband and doctor. A fight that was so bad, as it's told, had my grandfather leave the house for a few days, only to return with a new dinning room table and five chairs for a growing family. After the birth of the twin girls, taking the three kids and moving with my grandfather to his homeland, Poland. Without a word of Polish, money and work trying to outlast a winter in an apartment with three standing walls, which survived the war. Later arriving in Israel, following an idealistic Zionist husband, not speaking a word of Hebrew. She soon became the main supporter of the family, while my highly educated grandfather unwilling to "just take any job" stayed home. She worked long hours at a textile factory that left her physically exhausted and hospitalized. She followed my grandfather again, this time to the United States, no language, no friends. Only to rebuild life once more. When Itzhak passed, Lida, again moved. She returned to Israel searching for a new adventure. In her mid 70's she followed a new love, moving a to a kibbutz, ironically fulfilling her late husband's childhood dream. She concluded her life peacefully, basking in the endless Tel Aviv sun. With this strength and presence in your bloodline, you can’t help but feel invincible.

Lida - New York, USA

My work with The Ripple Project has shown me first-hand the psychological, physical and social post effects of trauma, even when the trauma is not your own. Around twenty years ago, I drove Lida, my mom and my wife from Washington DC to NYC, to stay with us for a bit. During the drive, in an uncharacteristic personal fashion, Lida told me how difficult it was for her to leave Israel for the US. She shared the tension the move created between her and my grandfather. They ended up moving as Lida became worried for Itzhak’s health. She was right, his physical well-being and post war trauma was taking a toll on him. She described in detail, a personal murky memory, a fight they both had around that time. I was a child, sitting in their living room watching her walk out of the apartment I loved so much, as my grandfather stated he is selling it. This was probably the first time I ever saw my grandparents quarrel so intensely. I remember the physical pain I felt. I was afraid of them leaving. Around that same year (I was around 8 or so), I began to suffer from uncontrollable episodes of shortness of breath. They were so severe that I was hospitalized for a bit which, must have, stressed my parents to no end. After a few weeks, the episodes disappeared as they appeared, over night. My parents joke that I was cured thanks to a doctor that yelled at me to go to school. This painful, confusing and sometimes shameful memory lingered in me for another two decades. On that drive I realized the bond between my grandmother and I was just as physical as it was emotional. This connection never faded.

Today I say goodbye to Lida’s body, but not her light, story, strength and love. Thank you for the umbrella סבתא (grandmother).

Lida and Zoe - Tel Aviv, Israel

Here is a poem written for Lida by my grandfather, Itzhak, for her 70th birthday (in Hebrew)

אשת חיל מי ימצא

אני מודה ליוצר האביב

שבימי בראשית

היה אלי מאד נדיב

והעניק לי אישית

מתנה לכל חיי

רעיה עצם מגופי

אם שלושת ילדיי

כולם תפארת דרכי

נולדו בן טלה ודג

נהדרים, נדיבי לב

החבורה יחדיו זה חג

אהבתהם משכיך כאב

ומעל הכל וכולם

אם סגולה

אם לב מסור וחם

לה שייכת את כל התהילה

אני מודה לאלוהיי

שבזכותו אני קיים

אבל בזכותה אני חי

אני כאן ולא שם

גיל 70 זה חג וטירחה

זה עצוב ונעים מגישים לך עוגה

נרות שנותייך דלוקים

כל שמחה וכל רינה

כולם מסובים וחבוקים

סימנים פריחה המופיעים בגינה

ברוך סימני סתיו

אתה מאיט את צעדיך

עלה שנושר הוא לא מזהב

רוב חייך מאחוריך

אנה רעייתי משוש ליבי

נצעד למרחקים ללא פחד

אני איתך ואת איתי

יד ביד תמיד ביחד

באהבה מסורה

בחיוך חם ונדיב

נרחיק מרה שחורה

בסתיו יונתי

!יהיה לנו אביב

ה-21 למרץ 1991