When COVID took hold of our lives confusion reigned supreme. Uncertainty became the norm and fear the standard. COVID was categorized as a “war” against an “invisible enemy.” We were told that in order to “stay safe,” we must follow simple hygiene guidelines and keep a distance from fellow human beings. The message is clear: you are safer alone.

And indeed, as countries began to open up and air got warmer we started stepping out. I thought I began to feel safe again. Then a clear-as-glass video surfaced, a collage of images of the inconceivable modern-day execution of George Floyd. I am not going to expand on social/racial/economic injustice, many sharper, smarter and more coherent words are being written and said. Who am I to talk anyway? After all, I am protected, and safe, no? I am white and part of a cushy middle class. I enjoy life's comforts and safety. Being Jewish in modern America is a confusing reality, after all Israel is an ally and the president’s son in-law is jewish. Does that make my family and I safer? From the noise and news clips of rising anti-Semitic sentiments like graffiti and a synagog shootings, moments of my own personal experience began to resurface. A slight ding in time that might have deemed insignificant, stubbornly stayed with me.

4th of July parade, Upstate NY 2018

A couple of years ago on an oppressively hot Catskills day, I took my mother and family to a small town upstate New York to a local 4th of July parade. It was a happy day, one of these days that feel as if all of life’s decisions were coming together, in the best possible way. My kids were running back and forth picking up candy from the street, I was a speaking loudly (as is unfortunately my custom) in Hebrew, all while trying to find my mother a shaded spot. We felt safe. At a certain point, I was approached by a burly, surly man who complained about my general rudeness, since I allowed my mother to share a space in a shaded spot that was “taken” by his family. He crudely explained that this was the custom of the place, where a family comes early to catch a shaded store front for the parade. I professed to not knowing that and apologized, while asking if my mother can stay shaded. The question was met with a look that is scorched in my memory, the man said: “I don’t know what language you are speaking, or where you are from, but you cannot be here.” As a dozen scenarios raced me like a familiar storm, I looked at my kids, mother and wife who were oblivious to the situation, we left. I did not feel safe.

4th of July parade, Upstate NY 2018

This seemingly mundane story is by no means a parallel to the tragedy of Mr. Floyd or the many others. But when I watch these body cams and phone videos my instinctive familiarity with the horrors rises to the surface as my trauma damaged epigenetic DNA is reminding me of another time and place. The image of a helpless man pleading for life and the deathly silence of the officers keep replaying in my mind as if I’ve personally seen this before. The gruesome images and infuriating helplessness begin to shift in geography, colors and language when replayed from memory. I know this story! My bloodline senses and recognizes the oppression of a militarized police combined with the helplessness of the victim. This was the story of my family also, one I have heard many times growing up.

Still from Itzhak Ginzburg interview (1995)

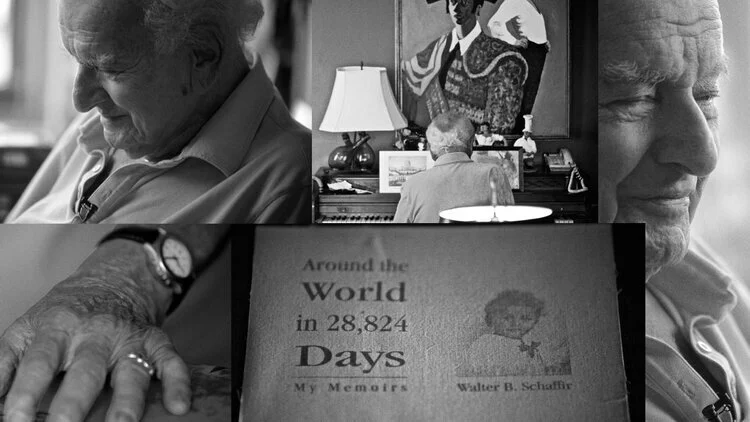

My grandfather’s youngest sister, at the age of 19, was executed by a policeman for an act of teenage public disobedience. After my grandfather’s parents refusal to leave Warsaw (1939 Poland), the young and brave sister went to personally ask them to join her and the other siblings in Bialystok (Poland), which was under “safe” Russian control. She believed that asking them in person would sway their minds. But before she even got to make the request face-to-face, she was executed without trial, without a jury, without a thought - all for not wearing a notorious jewish yellow star. She claimed not knowing of this law, but with hindsight of what she did next I believe she refused to wear a profiling badge. One that identified her as part of a single group and different from some of the peers she grew up with. She refused to carry a label of being an “other” in a place she once called home. It’s a human instinct to expect safety when we are home and in our neighborhoods and to some extent even our domicile. But that was no longer the case for Jews in Europe. This seemingly singular death is not a self contained incident. This murder and silence around it began a ripple effect that destroyed a (my) whole family. Who was the police protecting? Who was the Gendarm (military police) helping by profiling this teenage girl whose only crime was being born on the wrong side of the human genome? Did it make others feel safer? Did anyone speak out?

The parents she meant to bring with her ended up staying behind in Warsaw. The other siblings followed suit and left the safety of Bialystok to join their elderly parents, as it seemed to be the right thing to do. A decision that doomed the bloodline.

Walking to Brooklyn BLM 2020 protest

But there is a silver lining here. I do see hope. Until recently, when I closed my eyes and saw my great aunt laying dead in that train station I could not help but hear the silence around her. There were no voices and marches for the ones crying silently. But not anymore, people are no longer quiet nor blind. The horror stories that were once buried in books and oral history are now replaced with camera phones and live streaming. A shameful silence of the majority of that era is now replaced with a proud young generation of marchers worldwide. We cannot let the ones that were left chanceless, powerless and voiceless, whether then and now, disappear in silence. As young proud brooklynite protestor sign read: "White silence is violence,” together our scream will pierce the skies. We are immune as a herd.

Brooklyn BLM 2020 protest